When the Singaporean government asked local writers if they would agree to having their work used to train a large language model, it probably did not expect the country’s tiny literary community to react so fiercely.

An email sent late in March said that the National Multimodal LLM Programme (NMLP) aimed to address the bias of existing LLMs that have “disproportionately large influences” from Western societies. Singapore’s own LLM, trained on material produced locally, would have more accurate references to the nation’s history, colloquialisms, and culture and train on widely spoken languages, such as Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil, it said.

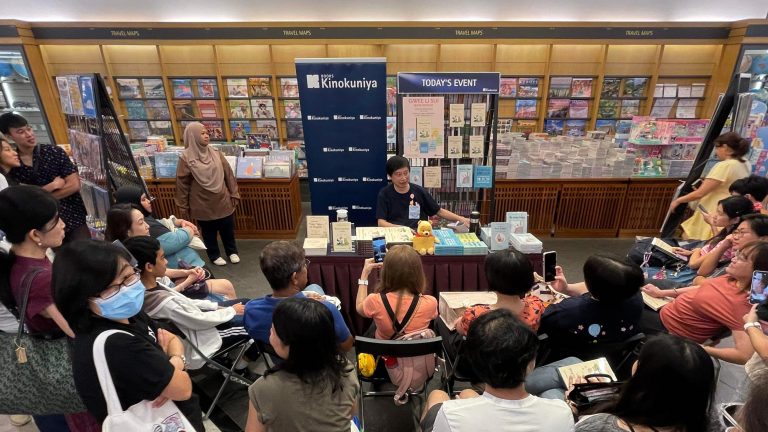

However, writers such as Gwee Li Sui, one of the city’s best-known literary figures, are not convinced.

“The stages of planning [for the LLM] before writers are even considered as worth consulting do not inspire confidence that my interest will be a priority,” Gwee, author of more than a dozen books, told Rest of World. There is also little clarity on how the works would be protected from being used “for purposes other than what is now claimed as public service towards cultural representation,” he said.

The email initially gave respondents 10 days to respond to a survey. But it had few details on compensation or copyright protection. So Gwee declined to let the LLM train on his works, including the first book written entirely in Singlish — a creole language that is a blend of Singaporean slang and English and is widely spoken in the country.

Gwee is one of several in the city-state’s tiny literary community pushing back against the government’s efforts to incorporate their works into the NMLP. The S$70 million ($52 million) project, launched last December, is touted as Southeast Asia’s first regional LLM and is part of Singapore’s ambitious plan to become a global leader in artificial intelligence by 2030.

The disgruntled Singaporean writers are part of a worldwide growing resistance to the use of published works to train AI technologies. Last year, U.S. comedian Sarah Silverman joined a class-action lawsuit with other authors against OpenAI and one against Meta, accusing the companies of copyright infringement for using protected work to train AI programs. In separate lawsuits, more than a dozen authors, including John Grisham and George R.R. Martin, have accused OpenAI of similarly infringing on their copyrights to train the popular ChatGPT chatbot. Publishers, including The New York Times, have also sued OpenAI and Microsoft for the same reason.

“Most LLM developers have taken the stance that web-scraped data is fair game to train on.”

Actions such as these are rare in Asia. Earlier this year, a Chinese court found that images generated by an AI service infringed the copyright of a science fiction character created by a Japanese studio. But as countries, including India, Indonesia, China, and Vietnam, develop their own multilingual LLMs, there is little clarity on what material is being used for training, what copyright protections authors have, and what — if any — compensation authors will receive.

Singaporean authorities have said the NMLP will be trained in 11 regional languages to capture Southeast Asia’s “unique linguistic characteristics and multilingual environment.” Building on the existing SEA-LION (South-East Asian Languages In One Network) family of LLMs, it will eventually form the basis for text-to-speech and text-to-image generative programs that can be used in translation and customer-service chatbots and other applications.

The email sent on behalf of Singapore’s Infocomm Media Development Authority (IMDA), the lead government agency driving the LLM project, said that all data contributed would be used solely for “research purposes.” It said it recognized that the development of AI and its impact on writers was a “hot-button issue” but made no mention of compensation.

Despite the writers’ criticism, “this level of proactive consent-seeking is quite rare,” according to Nuurrianti Jalli, an assistant professor at Oklahoma State University who has studied multilingual LLMs. “Most LLM developers have taken the stance that web-scraped data is fair game to train on, without getting permission from individual copyright holders,” Jalli told Rest of World. “So the Singapore government’s approach stands out as unusually considerate of writers’ rights. But writers understandably also want to know specifics.”

In response to queries, the IMDA referred Rest of World to its earlier statement to local media, where a spokesperson said the survey was “a research effort to advance understanding” of the project.

“The intent therefore was to consult the broader community on how we might approach this,” the agency had said.

Singapore authorities have historically had an uneasy relationship with the arts community, banning or censoring various works over the years for contravening official guidelines on race, religion, and politics. New laws have also cracked down on online content, while government grants prioritize creative works that do not “undermine the authority or legitimacy” of institutions.

Now, Singaporean writers are fearful of AI misusing their work with government sanction.

“The work of authors, translators, and publishers in Singapore and the rest of Southeast Asia ought to be treated with due respect,” New York–based literary organization Singapore Unbound said in a statement in response to the IMDA survey, which it did not receive. “It is not merely data for the machines, but the living tissue of our societies,” it said.

There are also “lots of gray areas” when it comes to copyright, and the legal status of training LLMs on copyrighted content is still uncertain, Peter Schoppert, director of National University of Singapore Press, an academic publisher, told Rest of World.

“It is not merely data for the machines, but the living tissue of our societies.”

“Neither Singapore’s text-and-data-mining exception nor the fair-use provisions in its 2021 Copyright Act would allow the training of LLMs that can then generate works without consent, credit, and compensation from copyright holders,” he said, adding that this is an interpretation that is yet to be tested in the courts.

Still, countries building multilingual LLMs are contending with a paucity of high-quality data to train on, so Singapore stands to gain by getting writers on its side, said Jalli.

“If key opinion leaders and writers withhold their work, the LLMs may have to rely more on lower-quality web-scraped content, which could limit their coherence and factual reliability,” she said. “So getting buy-in from the local writing and creative community is important for building public trust in the technology.”

While some negotiations with the government have taken place, few Singaporean writers and publishers think they will make much headway.

“The government is a juggernaut compared to us. If they want to ride roughshod over us, there is very little we can do,” said a member of the publishing industry, who asked not to be named, as they were still lobbying authorities on the matter.

Award-winning author Dave Chua is also resigned to the project moving ahead regardless of their sentiments, with compensation hard to come by. “I think they will just try to use works that are in the public domain and when authors give permission for their work to be used without compensation,” Chua told Rest of World. He said yes to having his material used in the LLM training, as he is “curious” to see what such an LLM would produce, he said.

Singapore’s founding father and former prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, famously said that “poetry is a luxury we cannot afford,” and this survivalist mindset has often dictated the government’s attitude towards the arts.

“Ultimately, our governance is a very pragmatic one,” Ng Kah Gay, editor at independent publisher Ethos Books, told Rest of World. “For us to hope that the government will see our value, we also have to show our relevance to the life and culture of our current society.”